The article based on the publication in German newspaper Dortmunder Kreisblatt describes the situation of Swabian pietists from Württemberg who came to the South Caucasus, which had become part of the Russian Imperium, at the invitation of Emperor Alexander I. The author outlines the history of German expatriates on that territory from 1818 to 1941. Despite cultural and linguistic differences, the newcomers and local peoples were in close contact in the cultural and economic spheres.

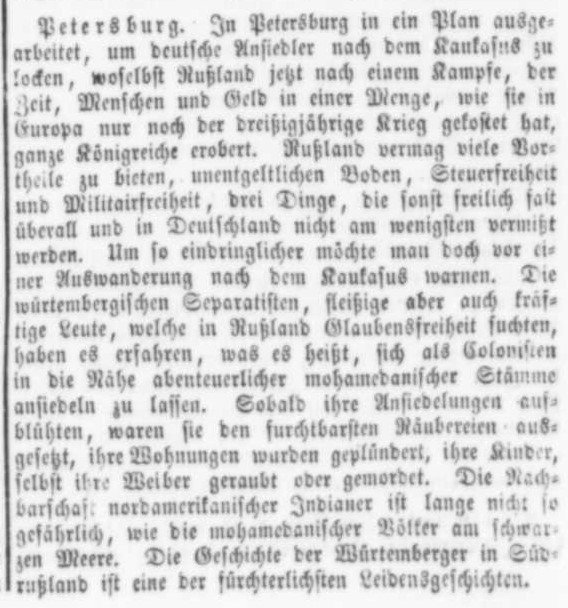

This item was published on 10 May 1860 in the Dortmunder Kreisblatt:

Dortmunder Kreisblatt №55 of 10 May 1860;

Original at the Institute for Newspaper Research

(Institut für Zeitungsforschung) in Dortmund, Germany

Petersburg.

In Petersburg ist1 ein Plan ausgearbeitet, um deutsche Ansiedler nach dem Kaukasus zu locken, woselbst Rußland jetzt nach einem Kampfe, der Zeit, Menschen und Geld in einer Menge, wie sie in Europa nur noch der dreißigjährige Krieg gekostet hat, ganze Königreiche erobert. Rußland vermag viele Vorteile zu bieten, unentgeltlichen Boden, Steuerfreiheit und Militärfreiheit, drei Dinge, die sonst freilich fast überall und in Deutschland nicht am wenigsten vermißt werden. Um so eindringlicher möchte man doch vor einer Auswanderung nach dem Kaukasus warnen. Die württembergischen Separatisten, fleißige aber auch kräftige Leute, welche in Russland Glaubensfreiheit suchten, haben es erfahren, was es heißt, sich als Colonisten in die Nähe abenteuerlicher mohammedanischer Stämme ansiedeln zu lassen. Sobald ihre Ansiedlungen aufblühten, waren sie den furchtbarsten Räubereien ausgesetzt, ihre Wohnungen wurden geplündert, ihre Kinder, selbst ihre Weiber geraubt oder gemordet. Die Nachbarschaft nordamerikanischer Indianer ist lange nicht so gefährlich, wie die mohammedanischer Völker am schwarzen Meere. Die Geschichte der Württemberger in Südrußland ist eine der fürchterlichsten Leidensgeschichten.

Petersburg.

In Petersburg a plan has been worked out to lure German settlers to the Caucasus, where Russia, after a struggle that has cost time, people and money in a quantity that has cost in Europe only the Thirty Years’ War, conquers entire kingdoms. Russia can offer many advantages, free land, tax exemption and military freedom, three things which, of course, are not least missed almost everywhere and in Germany. All the more urgently one would like to warn against emigration to the Caucasus. The Württemberg separatists, hard-working but also strong people who sought religious freedom in Russia, have experienced what it means to settle as colonists near adventurous Mohammedan tribes. As soon as their settlements flourished, they were subjected to the most terrible robberies, their homes were plundered, their children, even their wives, robbed or murdered. The neighbourhood of North American Indians is not nearly as dangerous as the Mohammedan peoples on the Black Sea. The history of the people of Württemberg in Southern Russia is one of the most terrible stories of suffering.

* * *

On May 10, 1817, the Russian Emperor Alexander I (1777–1825) approved the petition of 700 Swabian families for their resettlement in the South Caucasus.2 The city of Ulm was designated as a gathering point, from where the settlers were sent by ships down the Danube to Izmail. After the quarantine, they were accommodated for the winter in the already existing by that time Black Sea German colonies of Peterstal, Josefstal, Karlstal and other Swabian villages.

Only in August 1818, the settlers, accompanied by Cossacks, arrived in the South Caucasus.

Of the seven hundred families who left Ulm, only about four hundred reached the goal; some of the settlers died on the way from diseases, others remained in the Black Sea region. At the same time, about a hundred families from the Black Sea colonies joined the settlers. In Transcaucasia, the newcomers founded 6 settlements in Georgia and 2 – Annenfeld and Helenendorf – in Azerbaijan.

Helenendorf received the name in honour of the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (1784–1803), the daughter of Emperor of all the Russias Paul I (1754–1801) and Maria Feodorovna (née Duchess Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg; 1759–1828).

The colonists arrived at the appointed place at the end of 1818, so they were forced to spend the winter in Yelisavetpol (now Ganja) in Armenian families who also professed Christianity.

In the spring of 1819, on the Easter holidays, government officials determined the exact building site of Helenendorf – the former “Tatar settlement” of Hanahlar, where “except for a half-buried canal and pits in the ground, nothing resembled the former inhabitants.” Plots for yards were lined up along two streets.

The founders of the colony of Helenendorf were Swabian families (according to various sources, from 127 to 135), who arrived mainly from Reutlingen under the leadership of Gottlieb Koch, Duke Schimann, Jacob Krause, and Johannes Wuchrer. Initially, the colonists had to live in dugouts, for several years they lived in very difficult and even dangerous conditions, so in the first winter (1818–1819) only 118 families survived.

“It should be called Helenendorf – but first build earth huts” 4

During the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828, the Swabians had twice to find refuge in Yelisavetpol and Tiflis from the advancing Persians; both times Helenendorf was burned down by the Persians. In 1829–1830, deaths because of diseases (including plague and cholera) were twice as high as the birth rate.

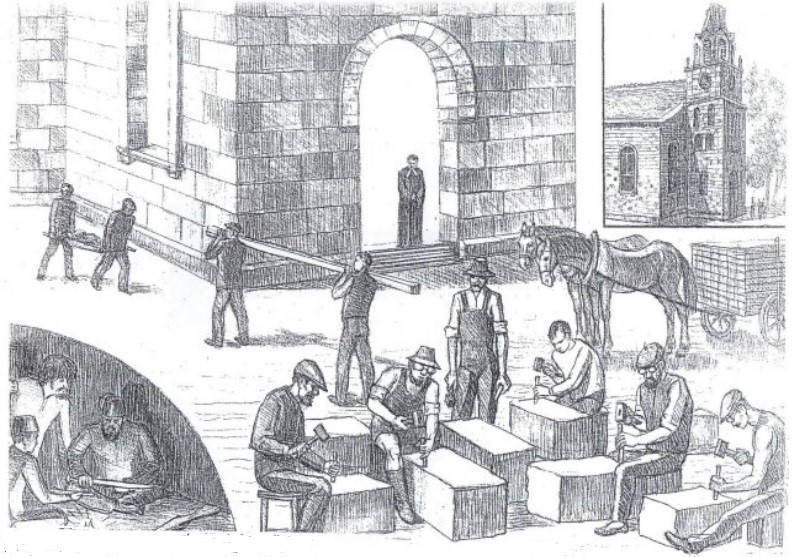

From the moment of the foundation of Helenendorf, divine services, sacraments and rites were conducted by a local teacher. In 1832, a pastor arrived in the colony from Hanover. In 1857, the stone St. John’s Church was built and consecrated in the village.

“If you want to secure your house – you have to build a church.

While the colonists built their church, the robbers sharpened their weapons.”5

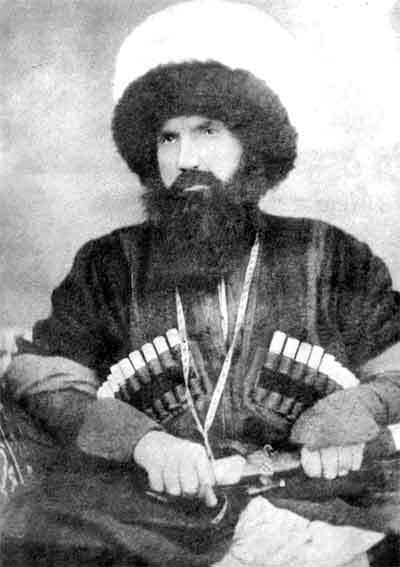

The first photograph of Imam Shamil,

taken in early September 1859 by Count Nostitz6 in Chiryurt.

In 1829, the Caucasian Imamate, a theocratic Islamic state that controlled Dagestan, Chechnya, Circassia and sometimes parts of Transcaucasia, arose to the north of German settlements. It existed until 1859, when, following the results of the Caucasian War (1817–1864), it was annexed to the Russian Empire.

The state was a confederation of free mainly ethnic polities united under the rule of the supreme ruler, the Imam. In 1834, Shamil (1797–1871) was elected Imam; he established himself as an intelligent, religious and brave man who mastered military tactics.

These commanders of the Russian army distinguished themselves in the Caucasian War:

– Lieutenant General Franz Klüge von Klugenau (1791–1851),

– General of the Cavalry Paul Graf von Grabbe (1789–1875),

– Lieutenant General Robert Friedrich Freytag (1802–1851),

– Adjutant General Alexander Baron von Wrangell (1804–1880),

– Lieutenant General Karl Theodor Hesse (1788–1842),

– General of the Infantry Alexander-Johann Baron von Neidhardt (1784–1845),

– Lieutenant General Johann Kaspar Fäsi (1795–1848),

– General of the Cavalry Grigory Khristoforovich Baron von Zass (1797–1883),

– Lieutenant General Johann (Iwan) Graf von Nostitz-Jänkendorf (1824—1905),

– Colonel of the Cavalry Arnold Sissermann (1824–1897),

– General of the Infantry Baron Georg Andreas von Rosen (1782–1841),

and many others.

The Meeting of General Klüge von Klügenau and Imam Shamil in 1837

The Imamat was the first example in the North-Eastern Caucasus where interethnic and interfaith marriages were practiced, protected by law. The Diwan Khan7 included the Ministry of Christianity and Religious Toleration. Churches were built in the Imamat – there were two of them in Vedeno,8 and next to it there was a Catholic church for Poles, many of whom were also defectors from the Russian army. Also, the Mountain Jews9 had their synagogue there. The Imam allocated land, forest, fields for arable land and haymaking to the families of the Greben Cossacks,10 who resettled with their families, livestock and property on the territory of Imamat, saying: “Live as you wish.”

Shamil fought against the mountain feudal nobility and abolished slavery. He ruled the state with the help of viceroys – mudirs and naibs,11 who, among other things, led raids on neighbours. They gave a fifth of the trophies obtained in the raids to Shamil; it replenished significantly the treasury of the Imamat.

Despite the hardships, the colonists managed to gradually improve their lives. In 1843, the German population of Helenendorf numbered 609. The national composition of the city in 1886 consisted of 1457 Germans, 160 Armenians, 8 Russians and 4 Tatars. According to the census of 1908, 3525 “souls” lived in the colony: 2384 – Germans, 400 – Russians (mainly Cossacks), 366 – Armenians, 300 – Persians (seasonal workers), 40 – Lezgins, 30 – Georgians, 5 people – “Tatars” (Azerbaijanis). At the beginning of the 20th century, five more colonies were founded mainly by Germans from Helenendorf: Grünfeld, Traubenfeld, Elizavetinka, Eichenfeld, Georgsfeld.

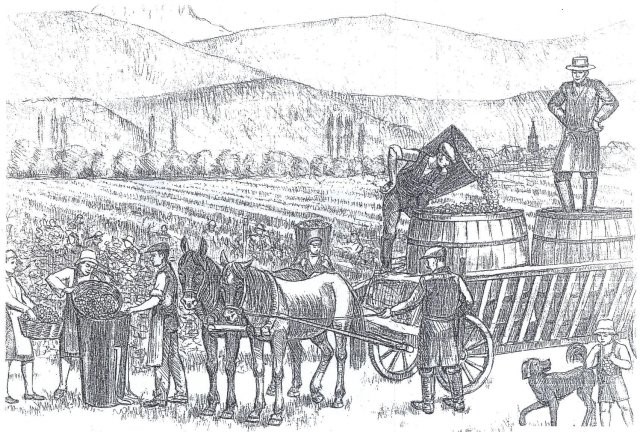

By 1875, the colonists had fully paid off the government loan (2,000 rubles per family) they had received in 1818 to move and equip their households and farms. By this time, the main occupation of the colonists was the cultivation of grapes and the production of alcoholic beverages – various varieties of vintage and table wine, cognac, champagne. The products produced in Helenendorf were sold by local firms “Hummel Brothers”, “Vohrer Brothers” and “Concordia” not only in Russia, in particular in Moscow and St. Petersburg, but also in Europe.

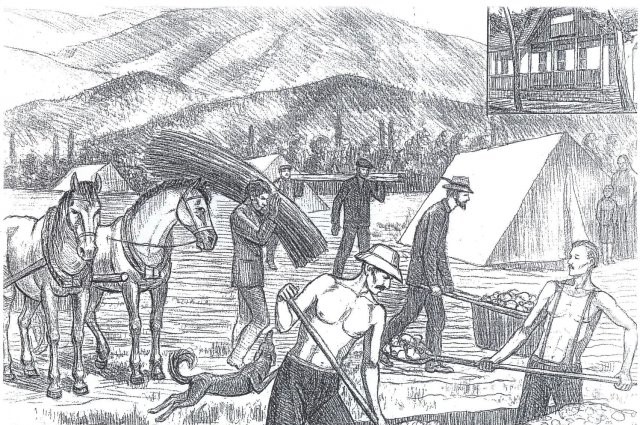

“Grape Harvest”12

Crafts had also been developed. By 1908, the colony had: 8 workshops for the production of horse-drawn carts (also supplied to the Russian army), 6 for the production of barrels, 9 forges, 9 carpentry and 6 woodworking workshops, 4 masters for sewing clothes, 4 painters and 4 stove makers, 3 locksmiths, one shoemaker.

The colonies of Azerbaijan were interconnected economically and culturally, the unofficial center was Helenendorf, which was the largest German colony in the Caucasus. In 1926 it had a population of 2157, Georgsfeld 936 inhabitants and Traubenfeld – 393.

In 1823, the first school was built, in which children studied in two classes. With the growth of the population, the school also grew, and the list of subjects studied in it also expanded. Since the 1890s, the study of the Russian language has become mandatory. In 1907, a boarding school was opened at the Helenendorf school to accommodate children from other German settlements of Transcaucasia.

In the 1920s, teachers from Germany were invited to work at the school. For example, music lessons at the Helenendorf School were taught by Alois Melichar (1896–1976), the future conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. Among the local teachers was Jacob Hummel (1893–1946), known for his scientific works on archaeology. In the 1930s, a prominent German writer and poet Franz Johann Bach (1885–1942) worked at the Helenendorf School.

Social cultural life in Helenendorf began with the foundation in 1893 of the “German Society” (German: Deutscher Verein), originally a men’s club with a library, a reading room and a bowling alley. Later on, amateur brass and string orchestras, a theatre studio were organized, which held concerts and performances both in the society hall, which could accommodate up to 400 spectators, and at various festive events, including in the Helenendorf public garden. In 1930, a music school with piano and string instrument classes was opened.

Various festivals were often held in Helenendorf, which brought together musical groups from all the Transcaucasian colonies (by the 1930s there were 21 colonies).

Despite cultural and linguistic differences, Germans and local peoples were in close contact in the cultural and economic spheres.

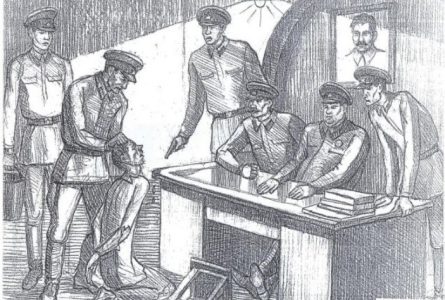

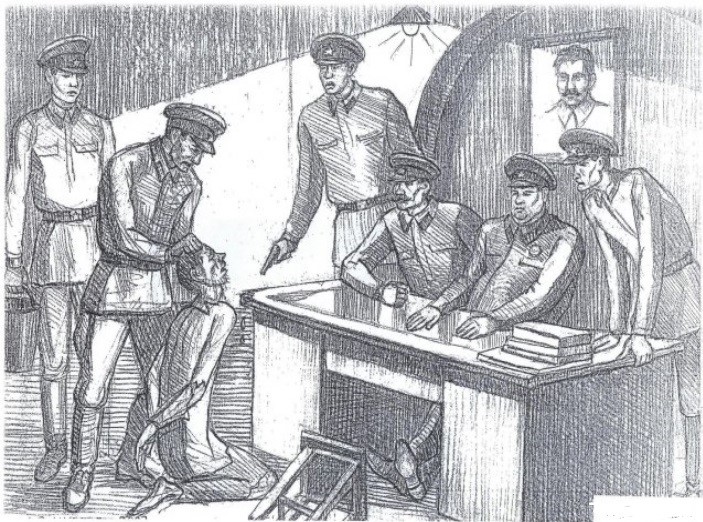

The cultural and economic decline of Helenendorf (from 1938 Khanlar) began with collectivization in the 1930s. Repressions did not bypass the colony, in 1933–1941 about 190 residents were arrested.

“The cruel 1937–1938 years13 – arrest“14

“Die Troika”15

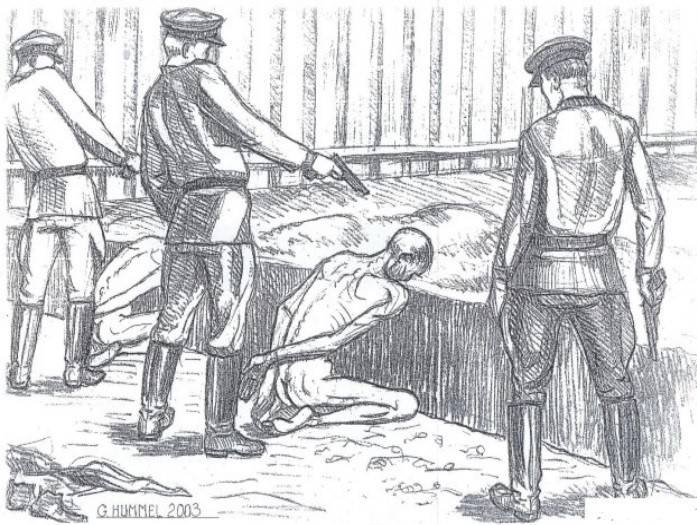

“Shot in the Neck”16

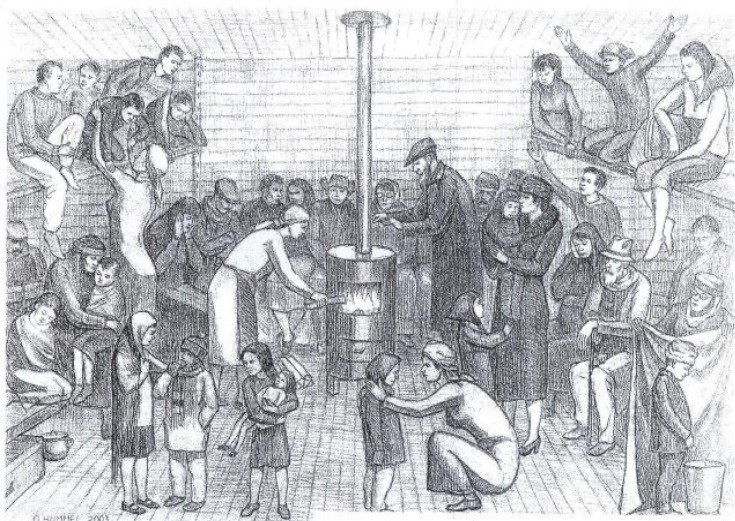

“In the wagon – resettlement to Siberia and Kazakhstan” (1941)17

With the beginning of the German-Soviet War (1941–1945), by order of the People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs of the USSR (No.001487 of October 11, 1941) “On the resettlement of persons of German nationality from Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia”, Khanlar’s Germans were deported to Central Asia, Kazakhstan and Siberia.

1. Im Originaltext ist ein Fehler vorgekommen: „in“ anstatt des Hilfsverbs „ist“. ←

2. The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, roughly corresponds to modern Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. ←

3. Günther Hummel (born May 8, 1927 in Helenendorf) is a Russia-German sculptor, teacher and musician. Between 1936 and 1939 he attended music and painting schools in Helenendorf and then completed his studies at the Technical School of Art in Baku until 1941. In the period between 1941 and 1945 there was a forced resettlement to Kazakhstan and from 1942 to 1945 a deployment in the labour concentration camp for Russia-Germans in the coal mines of Karaganda. From 1945 to 1950 he worked as a painter and music director in the “cultural house” of the coal mine. After his release, Günther Hummel also played in the symphony orchestra. ←

4. In German: „Helenendorf soll es heißen – aber erst mal Erdhütten bauen“ ←

5. In German: „Wer sein Haus sichern will – muss eine Kirche bauen. Während die Kolonisten ihre Kirche bauten, schliffen die Räuber ihre Waffen“. ←

6. Lieutenant General Johann (Iwan) Graf von Nostitz-Jänkendorf was an outstanding amateur photographer. ←

7. The Diwan Khan was the administrative body of the Caucasian Imamat. ←

8. Vedeno was the capital of the Caucasian Imamate. ←

9. The Mountain Jews, who live in the mountainous areas of the Caucasus, are the descendants of Persian Jews from Iran. Mountain Jews owned land and were farmers and gardeners, growing mainly grain. They also raised silkworms, cultivated tobacco and vineyards. ←

10. The Greben Cossacks was a group of Cossacks formed in the 16th century from Don Cossacks who left the Don area and settled in the northern foothills of the Caucasus. The Greben Cossacks were influenced by Chechen and Nogai culture. As Old Believers they maintained the liturgical practices of the Russian Orthodox Church as they were before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow (1652 – 1666). ←

11. The Caucasian Imamat was divided into mudirstans, which in turn were divided into naibstans. As a rule, one mudirstan included 4 naibstans. During the preparation and gathering of troops, the mudir supervised the organizational and military-administrative work of the naibs. During military operations, the naibs and their troops were subordinate to the mudir, and they operated under his unified command. The mudirs, in turn, operated under the leadership of the commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the Imamat, i.e., Imam Shamil. During the entire time of the existence of the Caucasian Imamat, more than twenty people became mudirs. ←

12. In German: Weinlese. ←

13. The Great Terror was Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin’s campaign to solidify his power over the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the state. It occurred from August 1936 to March 1938. The total estimate of deaths brought about by Soviet repression during the Great Terror ranges from 950,000 to 1.2 million. ←

14. In German: „Die grausamen 1937 – 1938 Jahre – Verhaftung”. ←

15. Troika means “a group of three” in Russian. The Soviet People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs set up “troikas” to issue sentences to people after simplified, speedy investigations and without a public and fair trial. ←

16. In German: „Genickschuss“. ←

17. In German: „Im Waggon – Aussiedlung nach Sibirien und Kasachstan (1941)“. ←

Dr. (Inst. f. Orient.) Walther Friesen

Ausbildungs- und Forschungszentrum ETHNOS e. V.

Dortmund, Germany