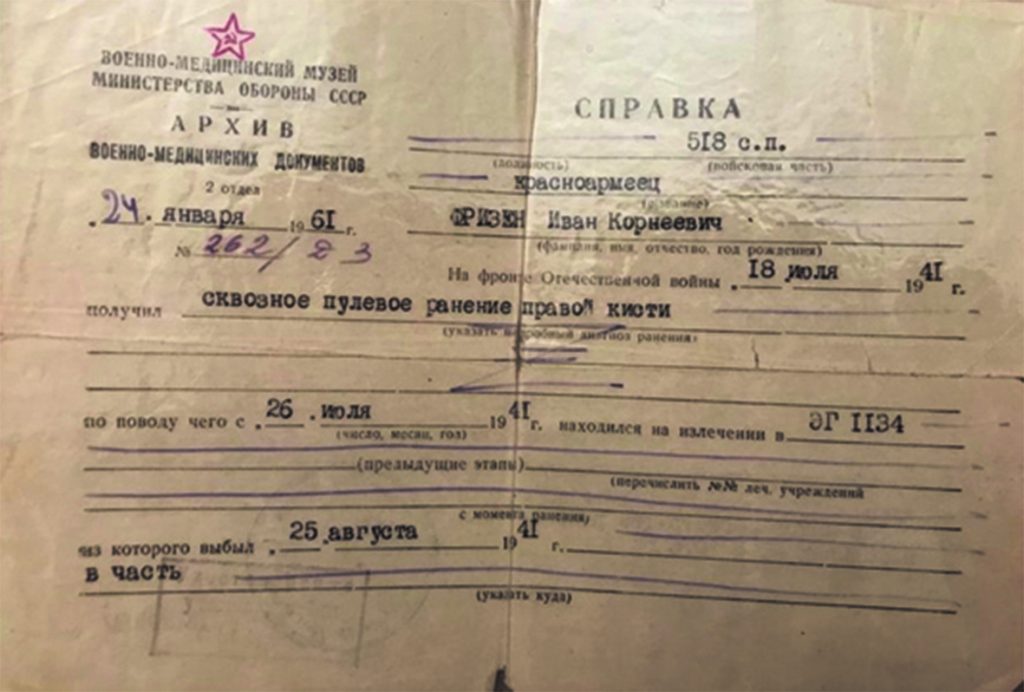

The article of Johann Friesen describes the first days of the Soviet-German War 1941–1945 and the Battle of Smolensk that was fought around the city of Smolensk between 10 July and 10 September 1941, about 400 km west of Moscow. His military detachment was among the few that managed to escape the pocket. He was twice wounded, but in July 1942 Johann Friesen was sent in a cattle wagon to a Siberian labour camp because of his German nationality.

The Hot Summer of 1941. The essay of Johann Friesen with microhistorical commentaries

Right now, I’m looking at the month of June in my calendar and it says: Summer has begun. The word summer awakens special thoughts and hopes. We gain new courage because the sun sends its rays to us longer and stronger. There is already a lot to eat in the gardens. Especially the children enjoy the first red berries. This is also how we feel when we read the Word of God or hear it in the divine service: then the soul thaws and draws new strength for the further path of life. During these long, warm June nights, memories keep rising.

I know that some of our readers do not want to hear how we young Russia-German men fared in the sad days of the summer of 1941. Recently, we experienced another war, this time in Iraq1). How much suffering, damage, wounded and dead brings such a terrible war. There are countries that believe that they can start a war in any country. This was also the case in the hot summer of 1941, when Stalin and Hitler started a major war.

We are not to blame for the fact that we Russia-Germans, including many Mennonites, had to take part in the greatest battles in the first period of the war. My grandfather, Johann Friesen, was a teacher; and at the same time he was a preacher of a Mennonite church. In 1929 he was arrested and exiled to the Solovetsky Islands. He perished there. Three uncles of mine were arrested and shot in 1937. The fourth uncle had been in the Gulag2) for 18 years. The same lot was shared by many Soviet citizens before the war.

in Solovetsky labour camp.

Photo of the late 1920s;

the watchman looks very much like Naftaly Frenkel (1883–1960)

“…there is a persistent legend that

the camps were invented by Frenkel.”

(Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr: The Gulag Archipelago, vol. II)

Nevertheless, we Russia-Germans did everything we could for Russia. The parents encouraged their children to do so. I was convinced that I had to defend my great homeland, the Soviet Union, and my closer home, the German villages in the vast Orenburg steppe. I would like to stress once again that many of our Russia-Germans who are now abroad do not want to hear about this time of horror.

Having participated in this war, I firmly believe that sometime our great-great-grandchildren should know that our Mennonites also had to participate in this war and that thousands and thousands of them were killed or wounded. And now I would like to report in more detail about this time of horror.

I was called up before the war. At that time, I was studying history at university. In our regiment, Russia-Germans made up a third. They had to fight against the fascists from the first day of the war. I would like to emphasize once again that we were not fighting against the German people, but against the SS fascists.

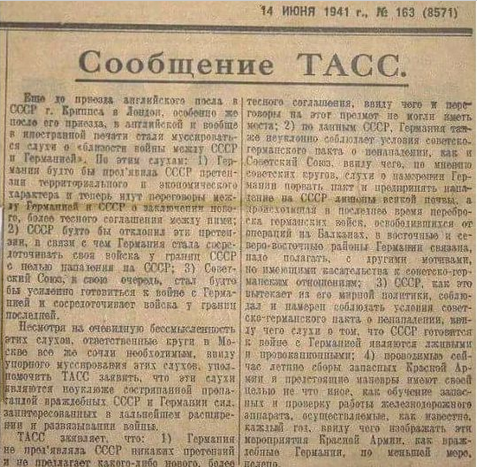

At the beginning of June, our division was moved to the state border. We received identification tags with home addresses, steel helmets, and new pistols. Although we knew and felt that the war was about to begin, we heard a statement from the News Agency TASS saying that these were merely rumours3).

On June 21, we bathed carefree in a river not far from the border, washed our clothes in it and watched a movie in the evening. Early in the morning, a roar tore me out of sleep. “Maneuvers, as announced,” I thought while looking at the clock. The pointer was on 4.

Around six o’clock we had to start and learned that Kiev and other cities had just been bombed and that the war had begun. Shortly afterwards, the regimental commander Pschenitschny waved me up to him and said: “Well, Friesen, we will fight together. Are you good at German?” I said that I had finished a German secondary school. “Then you should accompany me constantly,” he said. Then they gave us new uniforms, helmets, machine guns with knives, ammunition and, you should imagine that, even cream and brushes for shoes.

On the same day, at about 11 o’clock, I, as a good German-speaker, and 10 other Red Army soldiers were summoned to the divisional headquarters. They explained that about 25–30 km away, a group of German paratroopers landed in a cornfield. We went in search of it, and a couple of hours later we saw the enemies.

There was no time or tactical opportunity to fire, and we engaged in a bayonet battle. There were 11 of us, 6 of them. I still remember that bloody horror. We took two of them prisoner, and killed the rest. Our losses were 3 people.

I ended up with the prisoner in the staff car where the interrogation was going on. About two hours later, our train started west.4)

Under the incessant bombing we drove through Bryansk to Smolensk. From the conversations it became clear that the main direction of the fascists’ onslaught would be on Moscow, and not on Kiev, as previously assumed.

Our train stopped near Smolensk and we moved to Minsk, we were constantly bombed and our losses were considerable. And columns of soldiers from Minsk and Sluzk were coming towards us – tired, depressed, with dropped heads.

And then there was the Battle of Smolensk. We were stopped 20–30 km near the city, in a field. Konev3, the commander of our army, was standing there on a tank. In a calm, stern voice, he said, “You can’t retreat any further. The Motherland expects from us determination and victories in order to expel enemies from our territory.”

I will never forget Smolensk. It was July 17, 1941. After we had withdrawn from the border in the course of a few weeks, we received a strict order before we came to Smolensk to entrench ourselves and in no case to hand over the city to the Germans. Thousands of heavy guns, cannons, tank guns were shooting at us; hundreds of German planes were bombing the city. The sky was grey, everything was burning, the trenches were full of dead and wounded, human blood flowed in the trenches. So it lasted whole days and the nights. I was also wounded and saw no way out in this terrible situation.

I waited every moment for my death. We had been godless people for many years and did not think that God was our salvation. Suddenly, as if someone had pushed me, I remembered my mother, who had already died, how she often came to my bed in the evening and taught me to pray: “Dear Saviour, make me pious that I go to heaven. Amen.“ („Lieber Heiland mach mich fromm, daß ich in den Himmel komm. Amen.“) And what do you think, I began to pray. I asked God for help that I was still young and still wanted to live and see my relatives again. I raised my hands and asked the God for help. God heard it and I stayed alive.

Unfortunately, I soon forgot this case, because faith was the greatest crime during the Soviet rule. But often, very often, when there were such severe sufferings, I turned to God. I prayed a lot and begged the Lord to show his mercy and forgive us for not being so steadfast.

But they were such times. Not far from Smolensk we were encircled. The encirclement lasted ten days and only on the eleventh day we came out of that hell after heavy fighting.

I fought at the front for 392 days. Although I was wounded twice and became a war invalid, in July 1942 I was sent in a cattle wagon to Siberia in the taiga under strict guard.

I expected to be shot. But by Divine Providence, I finally came to Tula, 180 kilometres south of Moscow. For ten years I had to toil like a slave in the Stalin concentration camp in the coal mine. That was no less terrible than at the front. No less than hunger and heavy slave labour was for me the moral burden that we Russia-Germans were so mistrusted that we were considered helpers of the fascists.

The hatred was particularly expressive in the writings of Ilja Ehrenburg5). One of them, a pamphlet, was called, “Kill the German.” However, these articles directed against the mortal enemy also affected the Russia-Germans, who were also Germans and even officially accused of supporting the enemy6).

Yes, we did everything we could for Russia, especially to avoid even more trouble with the authorities. But one day I got under the coal and broke my foot, and then I got pneumonia. The NKVD people7) threw me on the stone floor and said, “He’s dying anyway.” In the difficult hours I often turned to God and prayed. And God helped me also that time. The Almighty sent me a kind Russian nurse who by chance came across me lying on the stone floor and insisted on bringing me into the concentration camp hospital.

I remained in the concentration camp until April 1952. Then I was allowed to go to my home village of Dejewka near Orenburg to my relatives, but I had to report my presence regularly to the local NKVD-Office until 19568).

Notes

1. The author is referring to the protracted armed conflict from 2003 to 2011 that began with the invasion of Iraq by the United States-led coalition, which overthrew the Iraqi government of President Saddam Hussein (1937–2006).

2. The GULAG (Russian: Glávnoje Upravlénije Lageréj “chief administration of the camps”) was the government agency in charge of the Soviet network of forced labour camps that existed from the 1930s to the early 1950s.

3.The author is referring to the report of the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (Telegrafnoye Agentstvo Sovetskogo Soyuza – TASS), published on 14 June 1941.

TASS report

Even before the arrival of the British ambassador, Mr. Cripps,* in London, especially after his arrival, rumours began to circulate in the English and foreign press in general about the “proximity of the war between the USSR and Germany.” According to these rumours: 1) Germany allegedly made territorial and economic claims to the USSR, and now negotiations are underway between Germany and the USSR to conclude a new, closer agreement between them; 2) the USSR allegedly rejected these claims, in connection with which Germany began to concentrate its troops near the borders of the USSR in order to attack the USSR; 3) The Soviet Union, in turn, began to prepare intensively for war with Germany and concentrated troops near the borders of the latter. Despite the obvious senselessness of these rumours, the responsible circles in Moscow still found it necessary, in view of the persistent exaggeration of these rumours, to authorize TASS to state that these rumours are clumsily concocted propaganda of forces hostile to the USSR and Germany interested in further expanding the war. TASS states that: 1) Germany did not make any claims to the USSR and did not propose any new, closer agreement, which is why negotiations on this subject could not take place; 2) According to the USSR, Germany abides as unswervingly the terms of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact as the Soviet Union, which is why, in the opinion of Soviet circles, rumours of Germany’s intentions to break the pact and launch an attack on the USSR are devoid of any ground, and the recent transfer of German troops liberated in the Balkans to the eastern and north-eastern regions** Germany is connected, presumably, with other motives that have nothing to do with Soviet-German relations; 3) the USSR, as follows from its peace policy, observed and intends to comply with the terms of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact, which is why rumours that the USSR was preparing for war with Germany are false and provocative; 4) the ongoing summer gatherings of red army reserves and the upcoming manoeuvres are aimed at nothing more than training reservist and checking the operation of the railway apparatus; they carried out, as it is well-known, every year, which is why it is ridiculous to portray these measures of the Red Army as hostile to Germany, to say the least.

4. Presumably, some military units of the Kiev Military District were relocated to the Western Special Military District to reinforce it.

5. Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (1891–1967) was a Soviet writer and journalist. In 1942, he wrote a pamphlet, titled ”Kill”: “The Germans are not humans. […] From now on, the word German causes gunfire. We shall not speak. We shall kill. If during a day you have not killed a single German, you have wasted the day. […] If you do not kill the German, he will kill you. […] If it is quiet at your section of the front and you are waiting for the battle, kill a German before the battle. If you let the German live, he will kill a Russian man and rape a Russian woman. If you have killed a German, kill another one too. […] Kill the German, thus cries your homeland.” Ehrenburg accompanied the Red Army forces during the East Prussian Offensive (1945) and criticized the indiscriminate violence against German civilians. However, his words were reinterpreted as license for atrocities against German civilians during the Soviet invasion of Germany in 1945.Passages from the “Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of 28 August 1941”:

6. „According to reliable information that has been gathered by military authorities, there are thousands and tens of thousands of saboteurs and spies among the German population living in different districts of the Volga Region who at a given signal from Germany must carry out explosions in the areas that are inhabited by the Volga Germans. … The State Defence Committee … must urgently carry out the resettlement of all the Volga Germans…”

After the issuance of this Decree, the Volga German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was liquidated and the Volga-Germans were completely deported from it. In the following months, deportation affected almost the entire German population living in the European part of Russia and the Caucasus, not occupied by the armed forces of Nazi Germany. The total number of Russia-Germans sent to forced internal exile was about 950,000, of which 30% died during deportation.

On 7 October 1942, the head of the Soviet state Joseph Stalin signed a top-secret Ordinance of the State Defense Committee № ГОКО-2383cc “On additional mobilization of Germans for the national economy of the USSR.” There is not a single paragraph in this document that contradicts (does not comply with) the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide proposed for signature and ratification by Resolution 260 (III) of the United Nations General Assembly of 9 December 1948 in Paris.

In Article I of the Convention, “The Contracting Parties” confirmed “that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.” “Soviet Germans” were “on the basis of nationality” imprisoned in concentration camps, hypocritically called “labour army” or “columns.”

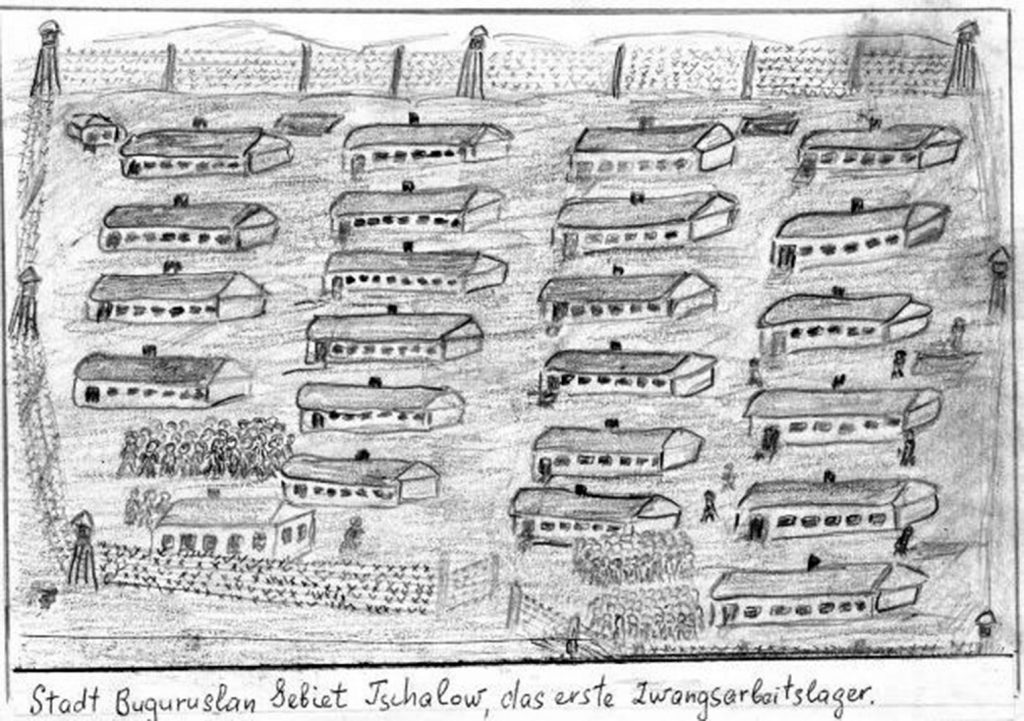

prisoner from 1941 to 1956; caption under the picture:

“Town of Buguruslan in Orenburg region,

my first concentration camp”

The Ordinance of the State Defense Committee № ГОКО-2383cc “On additional mobilization of Germans for the national economy of the USSR” compared with the provisions of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide:

TEXT OF THE ORDINANCE

“In addition to the rulings of ГОКО № 1123сс of 10 January 1942 and № 1281сс of 14 February 1942, the State Defence Committee DECIDES:

1. To mobilize additionally in working columns for the duration of the war all German men, including those aged 15–16 and 51–55, fit for physical labour, both resettlers from the central regions of the USSR and those from the German Republic of the Volga region; they have to be dispatched to the territory of the Kazakh USSR and the eastern regions of the RFSR; the same refers to those living in other oblasts, regions and republics of the Soviet Union.

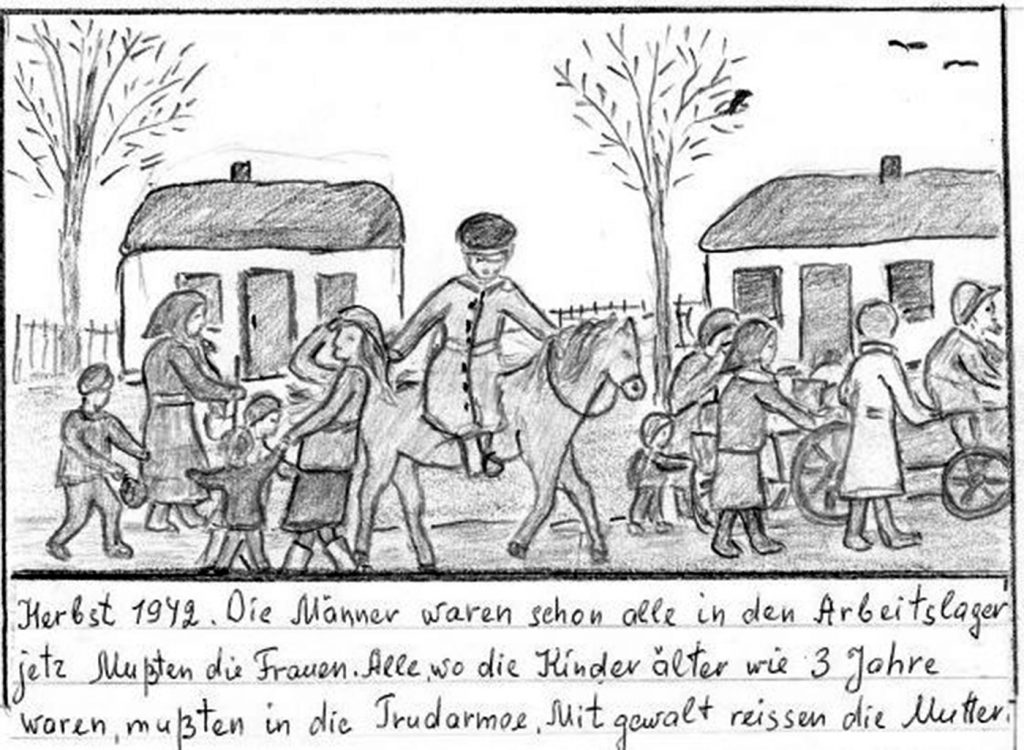

2. At the same time, all German women aged between 16 and 45 are also to be mobilized in working columns for the duration of the war.

7. Pregnant women and children under the age of 3 are exempt from the mobilization. The German men mobilized in accordance with this ordinance are to be dispatched to work for the enterprises of the trusts “Chelyabugol” and “Karagandagol” of the People’s Commissariat of Coal Mining. The mobilized German women are to be dispatched to work for the enterprises of the People’s Commissariat of Petroleum Industry in accordance with its priority tasks.”

TEXT OF THE CONVENTION

“…genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;”

COMMENTARY

German men and women of reproductive age were separated in the Soviet Union for many years: men worked 10–12 hours without days off in the mines (People’s Commissariat of Coal Mining), women – in quarries, brick factories; they also logged trees in taiga forests (People’s Commissariat of Petroleum Industry).

from 1941 to 1956; caption under the picture:

„Autumn 1942. All men were already in labour camps, now it was the turn of women. All those with children over the age of three were sent to the labour army.

Mothers [from children] were forcibly separated.”

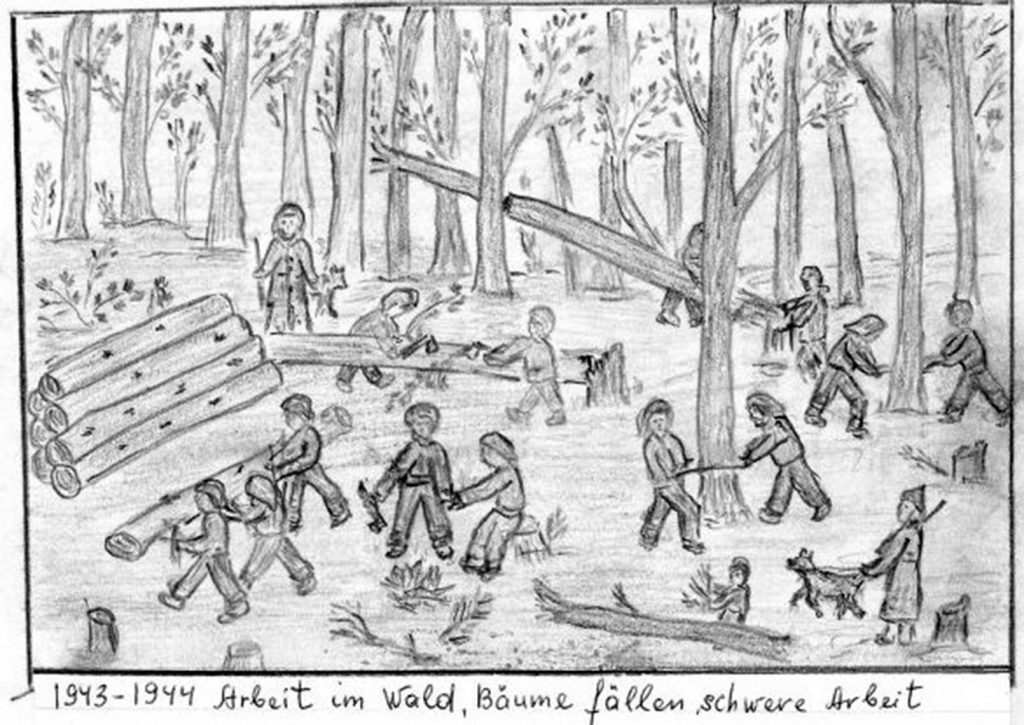

from 1941 to 1956; caption under the picture:

“1943–1944 work in the woods, trees logging – hard work”

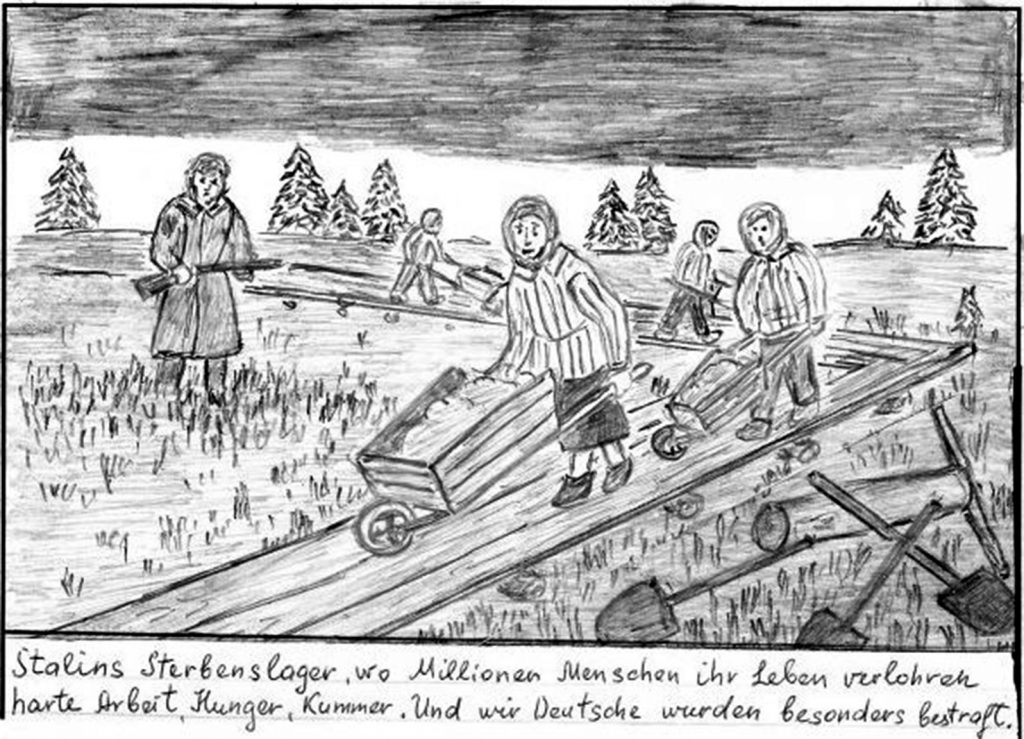

a GULAG prisoner from 1941 to 1956;

caption under the picture:

“Stalin’s death camps, where millions died;

hard work, hunger, fear. And we the Germans were especially punished“

After the war, according to the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR № 133/12 д. № 111/45 of 26 November 1948, „On criminal responsibility for escapes from places of compulsory and permanent settlement of persons evicted to remote areas of the Soviet Union during the Patriotic War“, the divisive repressive measures against the Russian Germans were further tightened:

“For the arbitrary departure (escape) from the places of mandatory settlement of these evictees, the guilty must be prosecuted. The defined penalty for this crime is 20 years of hard labour. Cases concerning the escapes of the evictees are considered in the Special Meeting of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR.

Those responsible for harbouring or facilitating the escape of evictees who have fled from mandatory settlements, those responsible for allowing the evictees to return to their former homes, and those who assist them in setting them up in their former homes will be prosecuted. The defined penalty for these crimes is imprisonment for 5 years.”

Until 1956, Germans were forced to regularly report in commandant’s offices or declare their “presence” in other “competent bodies” such as those authorized by the Committee for State Security.

In Tula region, German men worked in coal mines in Kireyevsky, Uzlovsky, Novomoskovsky, Shchyokinsky districts, German women – in quarries, and in brick factories. Young people were looking for an opportunity to meet; they were caught, especially at the crossings and bridges over the Upa River. Those who offered resistance were executed on the spot.

TEXT OF THE ORDINANCE

“4. The mobilization of the Germans has to be laid on the State Defence Committee and the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs with the involvement of local authorities of the Soviet government. The mobilization of the Germans has to be started immediately and finished in a month’s time.

5. All mobilized Germans are obliged to come to the assembly points in regular winter clothes, with a stock of laundry, bedding, mug, spoon and a 10-day supply of food.”

TEXT OF THE CONVENTION

„Genocide means any of the following acts:

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;“

COMMENTARY

The People’s Commissariat of Defence of the Soviet Union and the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs – the central body of the state administration of the USSR to fight crime and maintain public order and ensure state security – were responsible for this “mobilization”.

That is, the “Soviet Germans” were equated with particularly dangerous state criminals, with the only difference that the Soviet state did not guarantee them neither food (“… obliged to come” with “mug, spoon and a 10-day supply of food.”), neither clothes nor tolerable human existence (“… obliged to come … in regular winter clothes, with a stock of laundry”).

Daily rations in “labour camps” were allocated according to the food norms for prisons’ inmates. And that was for those who slaved away in mines, lumber mills, in quarries! From the memoirs of the academician Boris Rauschenbach (1915–2001), one of the founders of the Soviet cosmonautics:

“… Formally, I did not have any legal accusation based on some Criminal Code paragraph, the only charge without any legal justification was “German” and this meant an indefinite sentence. And so it was the GULAG – with bars, dogs, and everything as it had to be. Formally, I was considered to be mobilized for the “labour army”, but in fact that “labour army” was worse than corrective labour camps for criminals; we were fed much worse than prisoners, and we sat in the same zones, behind the same barbed wire, with the same convoy and all that. My unit – about a thousand people – lost half of its members in the first year, ten people died on some days. At the very beginning, we were simply put under a canopy without walls, and that was in the Northern Urals! The people had to endure frosts up to 30–40 degrees! We worked in a brick factory. I was lucky that I was not sent out either to the lumber mill or a coal mine, but, nevertheless, half of our factory workers died of hunger and unbearable work.

I survived by chance, because everything that happens in this world happens at the time God chooses. People died from a combination – hunger and hard work. If they didn’t have to slave away until complete exhaustion – in a brick factory, in a mine or as lumberjacks – they might have survived. But with the work we had, they couldn‘t survive.”***

TEXT OF THE ORDINANCE

“6. The Germans have to be prosecuted for failure to appear for the mobilization at conscription or assembly points, as well as for the arbitrary abandonment of work or desertion from working columns…”

TEXT OF THE CONVENTION

„…genocide means any of the following acts…:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;”

COMMENTARY

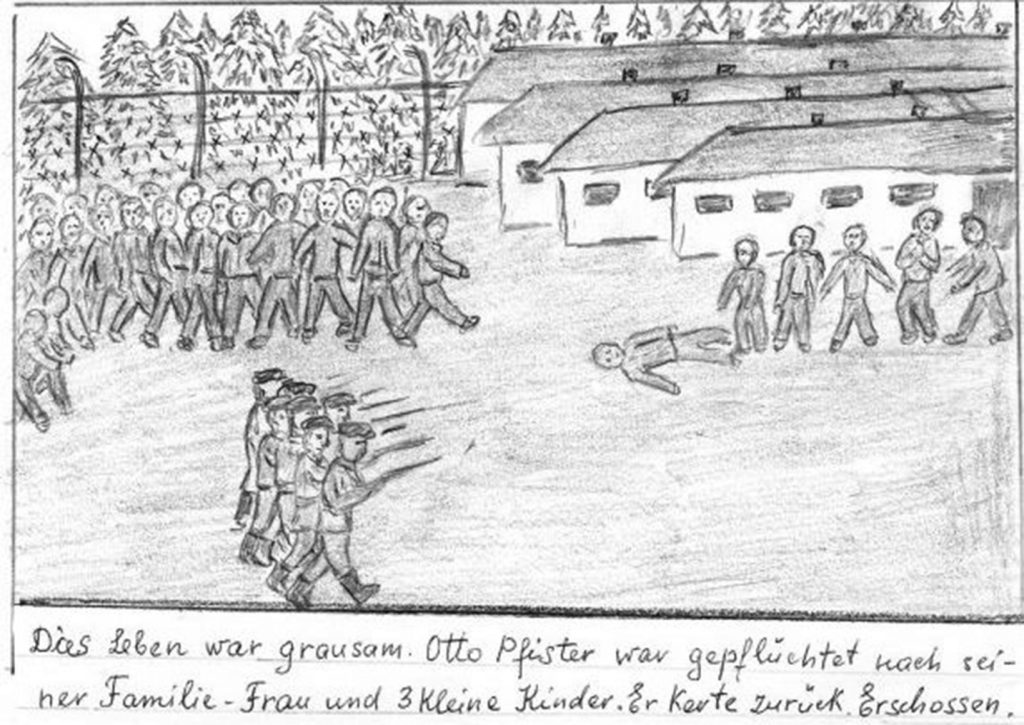

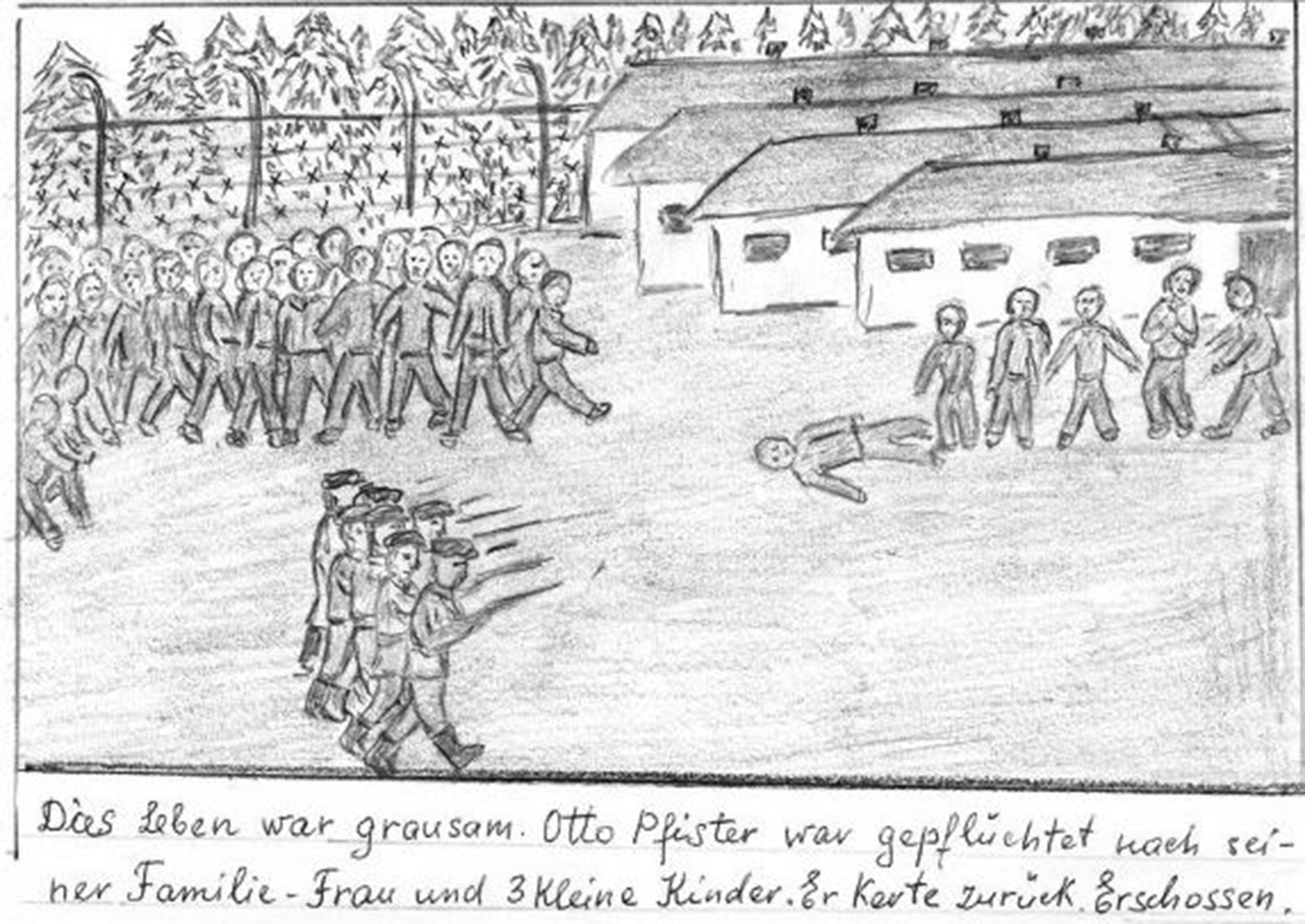

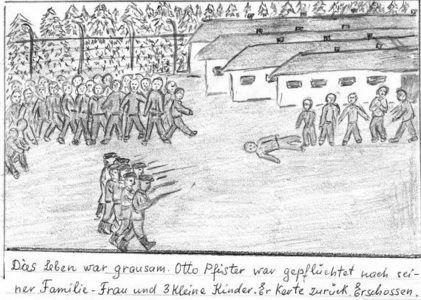

“Life was brutal. Otto Pfeiffer ran to his family – to his wife and three young children. He came back. (He) was shot dead.”

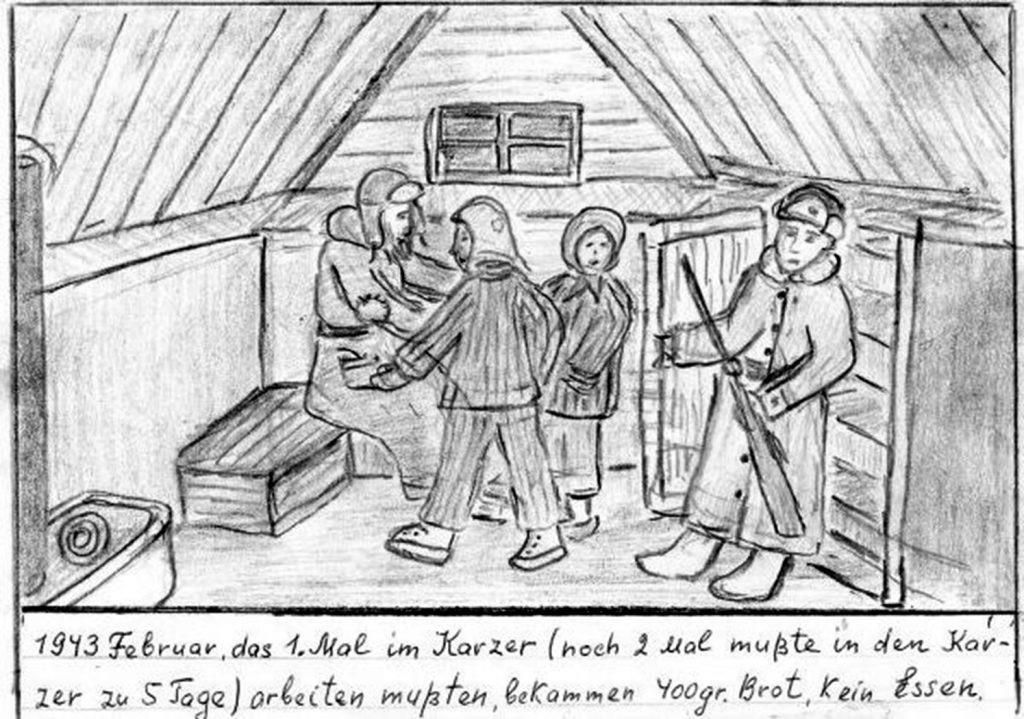

“February 1943. The first time in the solitary confinement (another 2 times was in the cell for 5 days). All the same had to work, received 400 gram bread. No food.”

TEXT OF THE ORDINANCE

“3. Available children over the age of three are committed to the rest of the family to foster them. In the absence of other family members, except for the mobilized ones, children are committed to their close relatives or German collective farms. The local Soviets of people’s deputies are obliged to take measures to accommodate the children of mobilised Germans who are left without parents.”

TEXT OF THE CONVENTION

„Genocide means any of the following acts…

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

COMMENTARY

This is the most hypocritical paragraph of the Ordinance. In the autumn of 1942, “German collective farms” did not exist. All national formations of Russia-Germans were completely eliminated by the autumn of 1941. Orphanages were overcrowded, there were no places for German children, and it was not “recommended” to accept them: “Who on earth is sending all of them to us? It’s not allowed to take them, you know.”**** The children were left to their own lives, many did not survive.

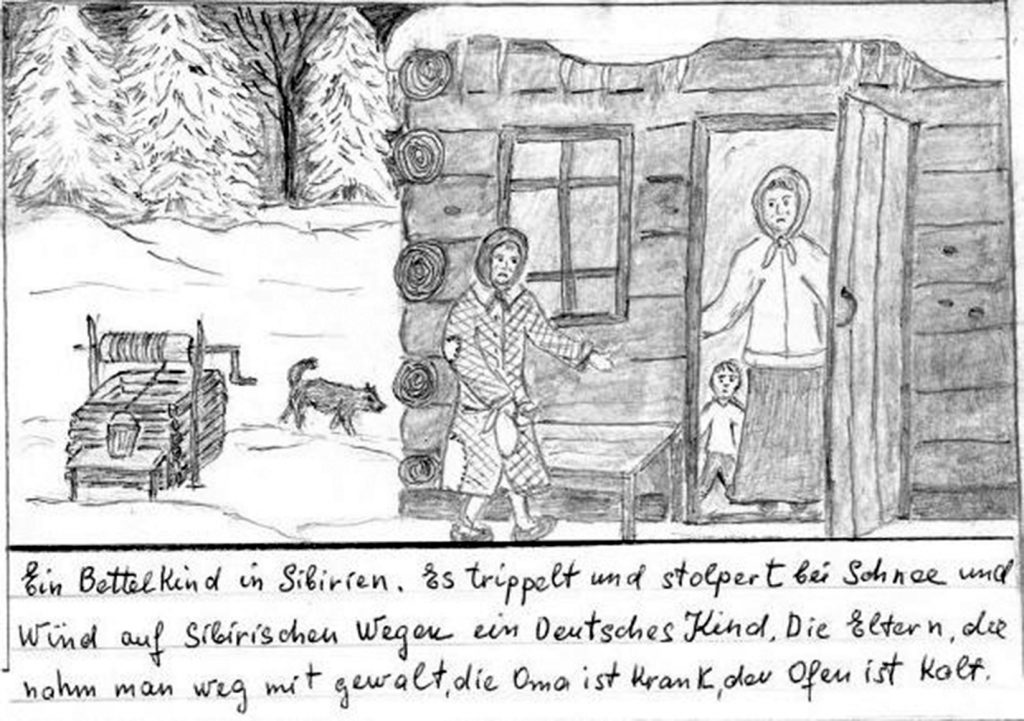

“A Begging Child in Siberia, 1942” is cited in the caption: “A German child is tripping and stumbling in snow

and wind on Siberian paths. The parents were taken away by force,

and Grandma lies sick, and the oven is cold.”

7. The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del, abbreviated NKVD) was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union. The NKVD undertook mass extrajudicial executions of untold numbers of citizens, and conceived, populated and administered the Gulag system of forced labour camps. It was responsible for the repression of the wealthier peasantry, as well as the mass deportations of entire nationalities to uninhabited regions of the country.

8. On 26 November 1948, the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR passed a decree on prohibiting Germans from returning to their former homes. They were banished “for eternal times” and had to stay in the prescribed labour camps’ settlements; the arbitrary abandonment of them was punished with 20 years of hard labour.

On 13 December 1955, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree “On ending the restrictions on the rights of Germans and their families who are in special settlements” (without return of the confiscated property). At the same time, they were banned from coming back to their former native settlements.

* Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (1889–1952)

** East Prussia and eastern regions of Poland are meant here.

*** Rauschenbach, Boris Viktorovich: Addiction. Agraf, Moscow 1997. (Раушенбах Б. В.: Пристрастие. Аграф, Москва 1997).

**** Wormsbecher, Hugo: Our Courtyard. AFZ ETHNOS e.V. Dortmund 2019; p. 52; ISBN 978-3-75042-980-2.

Johann Friesen

Johann Friesen (1921 [1920 – in the domestic passport] – 2011) taught German at the Polytechnic University and other institutions of higher education in Tula, Russia. The article was published in 2003 in German in the German-language Mennonite newspaper Der Bote ‘The Messenger’ released in Winnipeg, Manitoba by Mennonite Church Canada.

Lieber Lieber Lieber Opa! Sehr gut und interessant geschrieben!!!

… I remember so well, how You were dictating the words, and I was writing them down. It was almost like yesterday… but almost about twenty years before today…

What are You writing there? In the Heavenly Realm, mein Lieber Lieber Lieber Opa?!

!!!ויהיה נפשתך ומנוחתך בגן עדן

I miss You, Mutti, Omas and Opa Fima so very very very much!!!

🎈🖼🎈