The author is tackling the problem of national affiliation of Russia-German writers. Many of them were born in places of deportation, and the Volga region, the homeland of their parents, still sounds for them like a faraway paradise island, where they have never been, but would like to visit it. Antonina Schneider-Stremjakowa questions the widely held belief that “national literature is not created outside the national language.” She is of the opinion that the Russian-language literature of the Russia-Germans is the Russian literature, if only the language could be taken into account, but it is the literature of the Germans of Russia taking into consideration the ethnical self-identification of the authors and the spirit of the problems they are raising in their works.

Who are we, the Russia-German Authors, and What is our Literature?

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (1799–1837), Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (1814–1841), and Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol (1809–1852) are world-famous names. Even a halfway educated person in Russia knows that they are classical Russian poets and writers. But!.. Perhaps, some would say something more about it: Pushkin was not only a Russian, he was also an Arab! Lermontov had Scottish roots and Gogol – Ukrainian! And the opponents are right, because they are considering two factors: ethnicity and language.

With regard to Pushkin and Lermontov, syllogism is simple: they had not retained their ethnic language, were born and lived in Russia, wrote their works in Russian; that is, became representatives of the Russian nation (not nationality!) – Consequently, they are Russian authors who had shaped Russian literature.

And to whom does Gogol belong? There is no clear answer. Born in the Ukrainian Poltava Oblast, he kept his Ukrainian mother tongue, but he wrote all his works exclusively in Russian. Why? Because the russification of its indigenous peoples in the Russian Empire of the first half of the XIX century was in full swing. The Ukrainian folk traditions were not welcome. Russian, the language of the so-called “Great Russians” or French, which was also preferred, were used to be spoken in the noble families at that time. Ukrainian was the language of ordinary people (a kind of dialect), and the use of this language was considered unworthy by the nobles of the “high society”.

It is well known that in dialect it is impossible to achieve literary perfection. In the greater Russian language, Gogol felt aesthetically FREE and creative. He was born in Ukraine, retained his Ukrainian mother tongue, but wrote only in Russian and became the representative of the Russian nation (people). So, Gogol is a Russian and Ukrainian writer.

Ivan Franko (1856–1916), a Ukrainian poet, writer, ethnographer, and political activist called Gogol “a brilliant Ukrainian”, I would add – “a brilliant Ukrainian writing in Russian”. Are there any guidelines that would specify what criteria should be used to determine the author’s affiliation? Literature critics have developed corresponding theories and they are trying to convince us of their correctness, but I would like to present my arguments. Each author should be judged individually and thoroughly, as it is in jurisprudence. Based on the law and the administration of justice, lawyers can adjust the old jurisdiction within their authority. Therefore, sometimes different judgments are made in the same court case. The affiliation of each individual author and his works should also be determined individually.

Whose author is Anton Schneider (1798–1867) and other German writers?

The literary “anatomy” of Russia-Germans is similar to the «anatomy» of many national groups (ethnic groups) of Russia – Ukrainians, Tatars, Chechens, Buryats and others; therefore, Robert Korn’s question “But did they (Russian-speaking writers) become Russia-German writers” is opportunistic and provocative, since small peoples are not to blame for being “born small”: parents are not chosen.

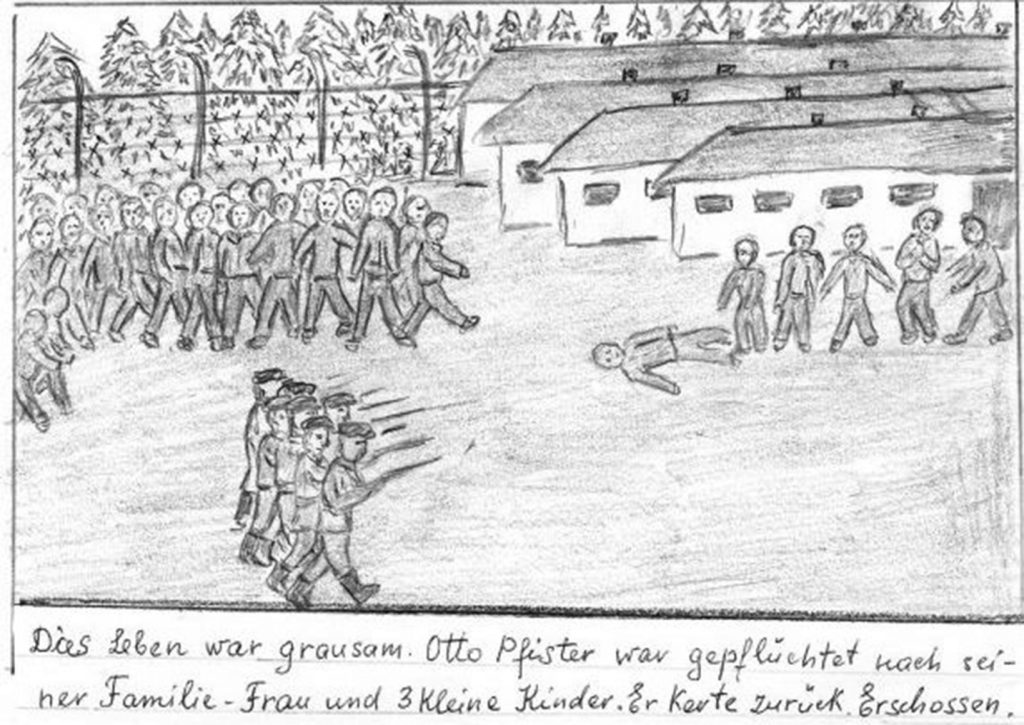

Russian-speaking Russia-Germans are, as a rule, Children of war, and it is quite natural that they absorbed the language of deportation – those places where the Germans of the USSR were forcibly evicted. According to Robert Korn, Russia-Germans include only those authors who:

1. Use in their work the German literary language or a dialect of the Volga-German language;

2. Were born in the German Volga region or spent a long time there and profess belonging to the ethnic group of Volga Germans;

3. Raise in their works the Volga-German problem, that is, events from the present and past of the ethnic group.“

Of these three points, I could to a certain extent agree only with the last one. I will never be able to write in “German literary language”, nor will I be able to pen in my Mariental dialect, since literary perfection cannot be achieved with its expressive means; and to demand German literary language from me, a Child of war, means:

• to restrict my aesthetic and creative freedom

• to prompt me to write primitively

• to deny me my nationality

• not to recognize the literature of the German war children

• to understate the fact of officially sanctioned disrepute of the Russia-Germans and the fact of considering them to be a second-class ethnic group before 1956.

Many Russian-speaking authors were born in places of deportation, and the Volga region, the homeland of their parents, still sounds for them like Moscow or Paris, where they have never been, but would like to visit it. The publicist Robert Korn himself cannot be attributed to the Volga-Germans, since he was born not in the Volga region, but in Kazakhstan. And then “logically”, should the “Russia-Germanness” be denied those born in the German villages of the Caucasus, Ukraine, Moldova, and the Baltic States?!

Many are of the opinion that language is not “the most decisive factor to assess the national affiliation of a particular literary work” Not everyone would agree to that.

Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861), a Ukrainian poet, writer, ethnographer, public and political figure, argued that “national literature is not created outside the national language.” The straightforwardness of this definition is disputable. The determining factor of the author’s belongingness is still the country in which he lives or has lived. And there are many examples of this. The opinion of Taras Shevchenko could also be refuted by the creative work of the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez (1927–2014), who received the Nobel Prize and created Colombian (!) literature in Spanish. In short, he’s a brilliant Colombian writer penning in Spanish.

The Russian-language literature of the Russia-Germans is the Russian literature, if we take into account only the language, but it is the literature of the Germans of Russia taking into consideration the ethnical self-identification of the authors and the spirit of the problems they have been raising in their works. Time will tell who could be called “a brilliant German author writing in the Russian language”. We need the works of unbiased critics (literary critics).

Who were these „authors writing in German”: Dominik Hollmann (1899–1990), Friedrich Bolger (1915–1988), Nelly Wacker (1919–2006), Robert Weber (1938–2009), Rudolf Jacquemien (1908–1992), Andreas Kramer (1920–2010), Nora Pfeffer (1919–2012), Lia Frank (1921–2012), Viktor Heinz (1937–2013), Alexander Beck (1926–2012), Friedrich Bolger (1915–1988), Johann Warkentin (1920–2012) and others? Whose author is Anton Schneider? He was born and lived in Russia, wrote in German Gothic script, but used to avail himself of Russian words that were part of the lexicon of autonomously living Volga-Germans: (рекомендовал [rekomendowal] → rekommandiert ‘recommended’; сараи [sarai] → Saraien ‘barns’; верста [wersta] → Werst ‘verst’ (1.0668 km); подвода [podwoda] → Podwoda ‘four-wheel horse-drawn vehicle’; кумыс [kumys] → Kumys ‘Kumis – fermented dairy product made from mare’s milk milk’; десятина [desjatina] → Desjatin ‘dessiatin’ (1.09 hectare); пуд [pud] → Pud ‘pood’ (16.38 kg); кабак [kabak] → Kabacke ‘tavern’; тройка [trojka] → Trojka ‘triplet’ (a traditional Russian harness driving combination, using three horses abreast, usually pulling a sleigh); аршин [Arschin] → Arschin ‘unit of length, about 690 mm long’; четверть [tschetwert] → Tschetwert ‘unit of length, 1/4 of Arschin, about 180 mm long’.

If we imagine Russian literature (culture) of the nineteenth century as a large chain, then Anton Schneider in this Russian chain is the same German link as the German link was in the Russian chain, but already of the Soviet period, the same as the above mentioned authors and many others. Consequently, these authors are Russia-German (if you will – Russian-German) writers of the Russian literature of the 20th century. The same Russia-German writer of Russian literature, but already in the first half of the 19th century, was the Russia-German Anton Schneider, because, speaking pathetically, he created national Russian literature in German. Perhaps that is why the images of Anton Schneider’s “Vorsteher” (high-level officials) are identical to the satirical images of the mayors depicted by one of the major Russian writers Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin (1826–1889): Dementy Brudasty, nicknamed The Music Box, Vasilisk Borodavkin (The Pimple), Ugryum-Burcheev (The Gloomy Сurmudgeon), who rebuilds the town into a totalitarian state.

If we imagine German literature (culture) as a large chain, the Russian-language literature of Russia-Germans would be in it the Russian link of a large, but now German chain. The chain is German, and the link is Russian!

We build a logical chain. Taking into account the citizenship and language of Russian-speaking Russia-Germans living in Germany, they are the Russian-German authors of the German literature, that is, the Russian link (and the subject of their works does not play a role here), while in the great chain of the Russian literature they are the German link of the Russian literature (as Tatar, Buryat, Chechen and other literature links).

Another thing are the authors (Russia-Germans) now living in Russia. They are Russian authors (by citizenship and language), as they create Russian literature in Russian language and represent the Russian nation, while authors living in Germany represent the German nation and create German literature, but in Russian language.

The Russian-language literature of Russia-Germans in Germany and Russia in the modern world is the irrefutable fact, and, as already mentioned, in terms of topics it can be not only about Russia-Germans. The depth of collective and individual consciousness is present in most of the works of Kurt Hein (1935–2016), Maria Schefner (b. 1958), Alexander Meißner (b. 1937), Vladimir Stehle (b. 1949), Alexander Rudt (b. 1952), Elena Seifert (b. 1973), Olga Seitz, Wjatscheslaw Sukatschjov-Springer (b. 1945), Swetlana Felde (b. 1967), Wladimir Eisner (b. 1947), Antonina Schneider-Stremjakova (b. 1937), Alexander Schmidt (b. 1949), Jakob Ickes (1926–2017) and many other authors; it depicts the mentality, which was consciously and unconsciously “absorbed” by the Germans in the places of their deportation from the local population and vice versa. So, the literature of Russia-Germans is also the history of the mentality of the peoples of Russia-USSR-Russia: Russians, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Altai people, Belarusians, Kerzhaks, Cossacks and others.

Is there a Future for German-speaking and Russian-speaking Literature of Russia-Germans?

We are alone, both in Russian and in German literature – we are not a chain, but a link. And in this literary solitariness is the phenomenon of the drama of an illegitimate people, a people without status. Robert Korn brings back voices from the past. It is important to do this, because every nation has its own “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign”,* and Russia-Germans are no exception. R. Korn has done a great job, but it seems that he hasn’t read the contemporary authors. And without knowledge of modern sources, it is impossible to talk about the history of literature, because the present day inevitably becomes the history of a certain era.

In 100 years (or even earlier), the literature of the Russia-Germans living in Germany will become only GERMAN, and the literature of the Russia-Germans living in Russia will become RUSSIAN, but in order to trace in the future the evolution and the tragic history of the culture and literature of the defamed people, it is necessary, firstly, to carefully study modern literature, like the scholars who are scrutinisingly study the literary legacies of Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837) or Vasily Shukshin (1929–1974); secondly, the status of Russia/Germans should be restored; but unfortunately, I don’t see a leader on the horizon.

And only with these two preconditions the long literary chain of the Russian nation as well as the long literary chain of the German nation could preserve the echo of the disappearing link of the literature of the unique ethnic group – Russia-Germans, because their literature is neither the inherent part of the literary history of Russia nor of the literary history of Germany. Otherwise, there will be NO-THING left of the Russia-Germans.

July 2021

Berlin-Buckow, Germany

Antonina Schneider-Stremjakowa

Russia-German writer. She lives in Berlin and administers

the internet portal devoted to the literary works

of Russia-German authors: https://www.rd-autoren.de/

Notes

* The Tale of Igor’s Campaign was written in the late 12th century by an anonymous author in the Old East Slavic language. It is considered to be a common Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian national epos.

Alexander Beck. Lyriker, Prosaiker, Übersetzer. Stammt aus bäuerlichen Verhältnissen, Kindheit und Jugend verbrachte er in Maienheim. Erste Gedichte erschienen 1938 im „Jungen Stürmer“. Nach der Zwangsverschleppung (1941) war er Traktorist, Schlosser, Klempner, Zimmermann. (Gebiet Nowosibirsk). Ende der 60er Jahre siedelte er in den Altai über. Vorübergehend Mitarbeiter in der „Roten Fahne, der „Freundschaft“ und des „Neues Leben“. Wurde Mitglied des Schriftstellerverbandes der UdSSR. Gedichtszyklus „Kunkel“, Meilensteine, Moskau, 1988, Gedichtszyklus in „Unser Wort“, 1991 u.a. Viele seine Gedichte sind echte Poesie. Wurde nicht seinem Talent entsprechend gewürdigt.

Поэт, очеркист, переводчик. Детство и юность провёл в Майенгейме. Едва успел окончить восемь классов немецкой школы, как был депортирован в Новосибирскую область. Работал трактористом, слесарем, жестянщиком, плотником. В конце 60-х переехал на Алтай.

Некоторое время был сотрудником газеты «РотеФане». Писать начал ещё в школьные годы. Активно печатался с 1962 г. в «НЛ», «РФ», «ХВ». Публиковался в трёх десятках коллективных сборников российских немецких писателей. Член СП СССР. Член Союза писателей России.

Александр Бекк был награждён медалью «За служение литературе» Ассоциации писателей Урала, Сибири и Поволжья за многолетнее служение литературе и в связи с 60-летием Алтайской краевой организации Союза писателей России. Церемония награждения состоялась 17 декабря 2011 г. в Белом зале Государственного музея истории литературы, искусства и культуры Алтая.

Всю свою жизнь и в особенности последние годы он работал над своей поэмой «Кункель в суетном мире», публикации которой так и не увидел, хотя очень мечтал об этом. Книга «Kunkel

im Weltgetriebe», стихи и поэмы Александра Бекка на немецком языке, издана в 2012 году. Первые послевоенные стихи были опубликованы в 1959 году. «Всегда на переднем крае», стихи и проза, Барнаул, 1983 (на немецком языке); цикл стихов, «ХВ», 1985, № 2; цикл стихов «Кункель», «Унзер Ворт», 1991 № 2; «Степная песня», М., 1981 (120 стихотворений на немецком языке); «Антология СНЛ», т. 2, А., 1981; «Книга для тебя», очерки, Барнаул, 1978 (на немецком языке); сборник «Созидание» М., 1981 (12 стихотворений в переводе на русский язык). «Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein» / «Я был, я есть, я буду». Sammelband. Барнаул/Barnaul, 2014 232 S. Zusammengestellt und verfasst von Alexander Pak. Nachdichtung – S. E. Kljuschnikow. Rezensentin – Doktor der Philologie, Professor Elena

Seifert., 2014 г., 250 экз., «Спектр»

Quellen: Edmund Mater. Deutsche Autoren Russlands

Kurt Hein. Geboren am 09.05.1935 in Jagodnoje an der Wolga. Von 1941 bis 1944 in Kasachstan danach in Sibirien, Altairegion. Absolvierte 1951 die Siebenklassenschule. Arbeitete als Dreher und Kombinenfahrer. 1956-1958 Wehrdienst in der Armee. Seit 1963 Lehrer für technisches Zeichnen und Malen. 1965-1971 Fernstudium an der Kunst- und Graphikfakultät der Pädagogischen Hochschule in Omsk. Bis zur Übersiedlung nach Deutschland unterrichtete Kurt Hein Kunst in Schulen. Schreibt Prosa auf Russisch seit 1999. Autor der Bücher: Рыжий конюх и красный маршал, рассказы, ISBN 3-933673-19-4, „Unsere Freunde – Наши друзья“ совместная книга с Корнеем Петкау. Иллюстрации собственные. Kurt Hein “Dort Damals”, ISBN: 9783732240807. Das Buch ist ebenfalls als e-Book zu erwerben.

Родился в 1935 году на Волге. С 1941 по 1944 жил в Казахстане затем в Сибири на Алтае. В 1951 году закончил семилетку. Работал в МТС токарем, комбайнером. После службы в армии с 1963 года работал учителем рисования и черчения, в 1971 году заочно закончил художественно-графический факультет Омского пединститута. До переезда в Германию в 1992 году преподавал в художественной школе села Подсосново Алтайского края. Живет в Бад-Вюнненберге. Пишет рассказы, воспоминания, печатался в русскоязычной периодической печати и в совместной с Корнелиусом Петкау книге «Наши друзья» (Славгород, 2003, 83 стр.) параллельно на русском и немецком языках с иллюстрациями Курта Гейна; в альманахах «Литературные страницы» (2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 на русском языке, 2004, 2006 на немецком языке) Литературного общества немцев из России.

Quellen: Edmund Mater. Deutsche Autoren Russlands